Information Literacy as Social Process

I would like to approach this topic in a speculative mode, in a flight of fancy, away from the more practical concerns of the LILAC Information Literacy Toolkit. It is in this flight that I hope to understand the nature of the discipline more richly — what our “setting to work” must entail. (Spivak 423) While conduction research on contemporary debates in information literacy pedagogy, I was moved by an antinomy succinctly composed by Jessica Critten, in her Introduction to Annie Downey’s 2015 Critical Information Literacy. With determined ardor she writes: “there is a sense that theory is impractical and practice is atheoretical” (Downey 2). Critten continues to outline this conflictual sensibility as the conceptual residue of another unresolved tension, between the natural sciences and the social sciences. Deciding that our work falls within the category of social science, she posits that “we could consider practice as possible evidence of theory and theory as a spark towards understanding;” there are emergent and dialectical properties to our work, and that the very nature of our discipline is a call to interdisciplinarity (Downey 3).

There is an objectifying call coming from the university at present: justify one’s discipline as a quantifiable science, or risk funding and support. These calls to standardization and hierarchy have created obstacles to the adoption of critical pedagogy. This was what so moved me about Critten’s idiomatic phrase. “There is a sense” that something must be done before it has even been considered what exactly it is, what exactly must be done. “There is a sense” that what is needed is a resolution to this tension between theory and practice, a resolution in which education would emerge as a process of social construction, in which information would be understood as not an object but a fallible network of statements and practices: bridging disciplines in situated praxis.

As an Information Literacy Fellow (2023-24) with CUNY’s Library Information Literacy Advisory Committee, I was asked to research and critically engage with CUNY’s digital ecosystem in order to find a proper digital repository for a sizable collection of teaching materials that would make these materials accessible and searchable to other faculty and librarians. This, alongside supplementary projects, provided me with fair insight into the state of information literacy pedagogy at CUNY. As a companion project to this practical work, I undertook a study of the main canon of critical information literacy scholarship. My own interests are related to knowledge production and media techniques post-WWII, and I was surprised: what I discovered in the course of my research was a surprising lack of writing about “information theory” in relation to “information literacy.” In reading about the adoption of critical pedagogical practices in relation to literacy, I had let wonder whether any parallel development had occurred in the theorization of information.

Allow a brief history:

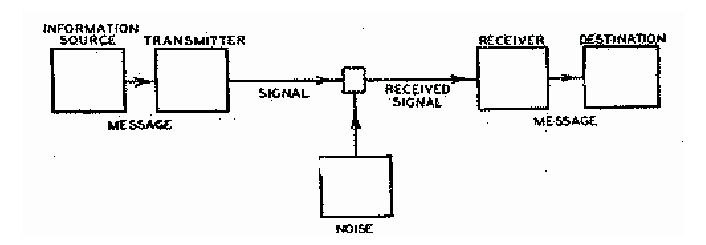

Information theory, stemming from early communications technology and refined as the interdisciplinary science of cybernetics in the post-War period, deals with communication as a process of sending and receiving messages containing information, information being defined by theorist Claude Shannon as “a measure of one’s freedom of choice when one selects a message” (Weaver, 9). Informed by the second law of thermodynamics which states that “energy dissipates and entropy increases” (Serres 1), this was an attempt to mathematically understand the fundamental structures of information and communication. And yet, in a review of the canonical information literacy literature the subject appeared to be essentially untouched. How are we to develop a pedagogy of information literacy without a thorough reckoning with the nature of information as it has been theorized in the West: a measure of freedom in contradistinction to noise, a war on entropy, and a site of control and resistance?

The term information literacy has its roots in a 1974 presentation by Paul Zurkowski. Then president of the Information Industry Association, Zurkowski wrote of the desire and need for greater collaboration between the private sector and traditional libraries in order to encourage and cultivate an information-literate public. After waxxing poetic on the structure and function of information as a kaleidescopic prism, Zurkowski reached his main, and physically underlined, point: “Anticipating these changing needs [new ways for people to process large amounts of information] and packaging concepts and ideas to meet them is a major economic activity” (Zurkowski, 5). Including cybernetic graphs to illustrate his idea of the publishing process in this information-dense ecosystem, Zurkowski continued to push an appealing economic thesis: “The marriage of the profit motive to the distribution [of] information is the single most important development in the information field since Carnegie began endowing libraries with funds to make information in books and journals more widely available to the public” (6). For Zurkowski, the “information literate” was an individual who was able to synthesize large amounts of information and instrumentalize them towards their occupation (6). It is this ability to understand the commodifiable value of information that defines the information-literate person.

Throughout the 1990s, and certainly since the development of Critical Information Literacy in the early 2000s, there has been a redirection of focus in order to contend with the implications of new media, respond to the standardizations of the Bush era, and integrate critical and postcolonial theories of pedagogy.

And so while the field has expanded, I argue that there is still a fundamental dissociation between the genealogy of information as a process (of energy transfer, of valuation), and what it means to teach information literacy. It appears as though the gap between the subjects of information theory and information literacy has never been more than cursorily attended. This raises serious questions. How is one to apply critical frameworks, teach the nature of media and transmission, and comment on the ways information transforms society, without reckoning with that fundamental ideological root of contemporary discourse on information — namely information theory and cybernetics? There has been movement to recognize these connections in relationship to information literacy, but typically through a refracting lens, not explicitly citing information literacy but speaking around and through it. Infrastructure studies, Critical Data studies, as well as new philosophies of techne, cognition, and epistemology all cite these foundational theories in order to show the ways our mental formations and social milieus are informed by technology and ideology.

It is this awareness, paired with the critical pedagogy movement of Paulo Friere and others, that can provide an imaginative network of methods for transmitting information literacy today. Critical pedagogy is a necessary mirror to information theory – for as Bernhard Geoghean outlines in his Code: From French Theory to Information Theory, information theory is based on its own fundamental veil of neutrality. He writes, “Like the dreams of sublime communication that shaped the early histories of networked railroads and telegraphy, dreams of cybernetic post-humanism depended on disappearing the bodies of native persons and other subjects regarded as less than human” (Geoghegan 10). Taken up by the social sciences and applied initially to linguistics, anthropology, and psychoanalysis, information theory served as a mathematical utopianism – in which communication could be represented by bits and bytes, and behavior could be predicted algorithmically. It is these theories that uncritically underly the algorithmic structures of image recognition technologies, generative AI, and watch recommendations.

How can someone tackle all of this in a single-class session in which students are tasked with learning how to use a database? Or how to craft a research question? How is information to touch its conceptual existence while always already needing to be instrumentalized and commodified? It can feel like these origin stories call into question the entirety of our knowledge structures, the bases for our behavior — and how is anyone supposed to do anything then, when so much theory is apparently needed in order to provide justification for action?

I believe this is the crux of the dilemma in our field today. What is required for the development of literate students is a wholesale engagement with the ways in which they learn, on a theoretical level. We must understand information literacy as a social science rather than a natural science, and as a networked and embodied process rather than an individualistic and determinate ability. This means identifying patterns of social construction and reification, and participating in tangled discourse with our colleagues and students. We are constantly contributing to this discourse we call our world, and as such must incorporate critical techniques of knowing into our practices.

Bibliography

Downey, Annie. Critical Information Literacy : Foundations, Inspiration, and Ideas. Library Juice Press, 2016.

Geoghegan, Bernard Dionysius. Code : From Information Theory to French Theory. Duke University Press, 2023.

Serres, Michel. “The Origin of Language: Biology, Information Theory and Thermodynamics.” Oxford Literary Review, vol. 5, no. 1\2, 1982, pp. 113–24, https://doi.org/10.3366/olr.1982.008.

Shannon, Claude Elwood, and Warren Weaver. The Mathematical Theory of Communication. University of Illinois Press, 1949.

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. A Critique of Postcolonial Reason : Toward a History of the Vanishing Present. Harvard University Press, 1999.

Zurkowski, Paul G. The Information Service Environment Relationships and Priorities. Related Paper No. 5. 1974.

0 responses to “Information literacy as social process”